When and how did the marae structure develop?

New research by two Swedish archaeologists suggests that ritual spaces in Eastern Polynesia were quite different before megalithic ahu/marae temple structures developed in the 13th century.

Summary

Have two Swedish archaeologists finally figured out how and when marae structures developed in Eastern Polynesia?

In a recently published paper, Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin of Uppsala University revisit their own excavation of a key Rapa Nui site, the early settlement of Anakena and Naunau East, excavated in 1987-88.

Their research paper is entitled:

Anakena Revisited: New Perspectives on Old Problems at Anakena, Rapa Nui. Chapter 6 in the Prehistory of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). In: Towards an Integrative Interdisciplinary Framework, edited by Valenti Rull and Christopher Stevenson. Springer, 2022.

Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin's study is chapter 6 in the Prehistory of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Towards an Integrative Interdisciplinary Framework, edited by Valenti Rull and Christopher Stevenson, and recently published by Springer.

The authors argue that early Polynesian ritual space was an area where various rituals took place, marked off from the settlement, perhaps by a stone upright tower and some sacrificial towers, but without the later stone platforms that define the marae and ahu after 1300 AD.

A long-term research focus

The impressive megalithic temple structures of Hawai'i, the Marquesas Islands, the Society Islands and Rapa Nui, called in the local languages marae, ahu or heiau, quickly became the focus of research when professional archaeologists began working in Eastern Polynesia in the 1910s and 1920s. It was thought that these temples, and the architectural sequences found in individual structures or between sites, could be the main basis for a cultural chronology. A few researchers also speculated that they held the keys to the cultural area from which the Polynesians came.

Two different notions about the origin of these complexes developed among scientists. The first generation believed that different concepts of ritual space had developed with Polynesian culture in the western islands, which emigrants brought with them to Central-Eastern Polynesia and then to the outlying islands of Polynesia: Hawai'i and Rapa Nui. The open gathering places, sometimes with an upright stone in the center, in Western Polynesia called malae, became the model from which the Eastern Polynesian stone temples had evolved. The space, where the rituals and dancing took place, was defined by stone walls or a platform with stone tiles. The central ritual focus became an altar on one side, and later grew to increasingly larger platforms raised above the plaza. This perspective necessitates that these stone temples first developed in Central East Polynesia, and were later brought as a cultural package to the outer islands of Hawai'i and Rapa Nui when those islands were discovered and settled.

The second generation saw the megalithic stone temples as a break with earlier concepts of a religious space, first developed on the outer ends of the Polynesian triangle of Hawai'i or Rapa Nui, and then "diffusing" this architectural design to the Central East. Polynesian Islands. In this perspective, ahu platforms on Rapa Nui and heiau complexes on Hawai'i should predate those of Central East Polynesia, i.e. the Society Islands.

It took many years before archaeologists began excavating ritual structures in a serious attempt to date their original construction. The first excavations took place on Rapa Nui and the Marquesas Islands with the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the Eastern Pacific in 1955-56. A few surveys were done in the Windward Society Islands by French researchers in the 1960s. In Hawaii, extensive study and excavation of heiau complexes took place in the late 1980s.

The only exception to this general trend was the work on Rapa Nui, where reconstructions of the famous ritual platforms, called ahu with the giant moai on top, were carried out from the mid-1960s onwards.

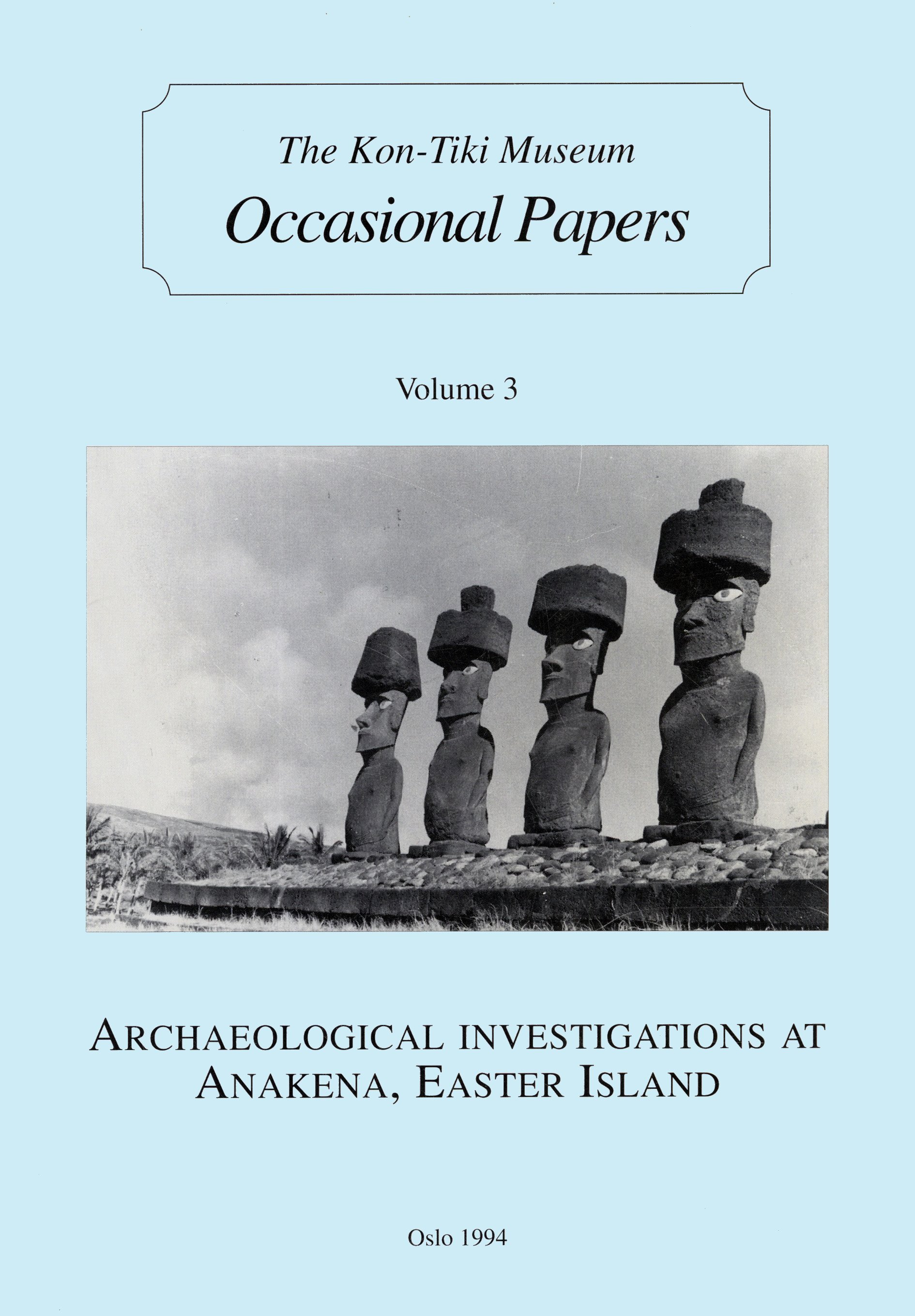

The restored Ahu Naunau, Anakena, Rapa Nui, with the Kon-Tiki Museum's excavation of an early ahu in front (Photo: Walter Leonardi).

Building a chronological framework

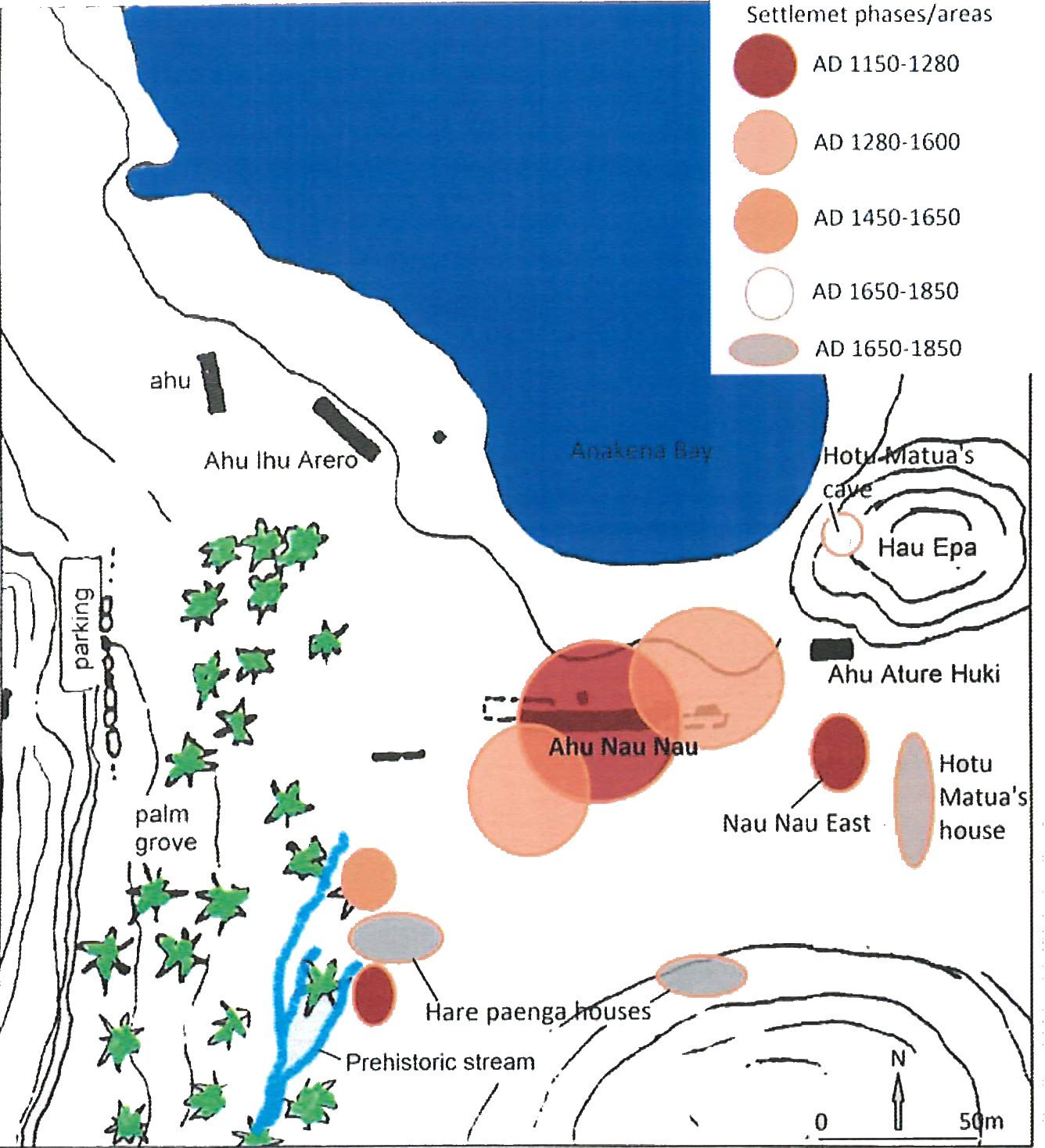

Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki Museum returned to Rapa Nui in 1986-88 to search for early settlement sites, with Paul Wallin, Helene Martinsson-Wallin and Sonia Haoa as key investigators.

The project located and excavated what is to date the earliest settlement on the island and also two earlier ahu structures beneath Naunau. An ahu of similar size and construction was found during the excavations prior to the restoration of Ahu Tongariki in 1993-94.

In the late 1990s, Helene Martinsson-Wallin and Paul Wallin initiated new investigations of ahu foundations on Rapa Nui with the specific purpose of building a better chronological framework.

In 2001, Paul Wallin launched the project Local Developments and Regional Interactions: The Huahine Archaeological Project, a collaboration between the Kon-Tiki Museum, the Ethnographic Museum in Oslo, the Service de la Culture et du Patrimoine in Tahiti and the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Hawaii.

The aim of the project was to establish a chronological framework of the marae structures on Huahine, Leeward Island, and to control the wider context of the local project by re-dating charcoal from periodic survey of marae in the Windward Islands. These projects confirmed that the ahu foundations on Rapa Nui had developed some time after 1300 AD. and that the earliest date so far from the Society Islands marae is around 1450 AD, perhaps later.

Photo of the first ahu in the Tongariki area, Rapa Nui, taken in 1993 (Photo: Reidar Solsvik).

No more marae

Archaeologists have claimed that the first settlement of Rapa Nui was around 1200 AD, about 100 years before the first dated construction of an ahu foundation. What did the ritual space of the earliest settlers look like?

Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin suggest, through a reinterpretation of their excavation of the site Naunau East, Anakena, Rapa Nui, that early ritual spaces "were particular sites that incorporated natural landscape features and culturally shaped features with ritual connotations that varied in form and function » (Wallin and Martinsson-Wallin 2022:134).

"Based on archaeological research, it is likely that early Polynesian ritual spaces contained posts, poles, planks, images, fires, burials, feasts, waste pits and storage elements. The traditional ahu/marae construction consisting of stones developed later, but the early functions were continuously incorporated into the marae structures/concepts, when they became monumental in Central East Polynesia around AD 1400 (Wallin and Martinsson-Wallin 2022:134).

The authors compare their finds at Naunau East, Anakena, Rapa Nui, with similar finds in Norfolk by Atholl Andersson and the excavation of a coral upright outside a rounded house at Vaito'otia/Fa'ahia, Huahine, Society Islands, by Yosihiko H. Sinoto.

This hypothesis is indeed interesting and may have finally bridged the gap between the well-known stone structures called marae/ahu/heiau, and the preceding Polynesian ritual concepts in a very tangible way.

A famous 1970 paper by Kenneth P. Emory, the dean of marae studies in Polynesia, summarizing his investigations into the origins and development of Polynesian ritual spaces was titled A Re-examination of East Polynesian Marae. Many Marae Later. As a conclusion to Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin's article Anakena Revisited: New Perspectives on Old Problems at Anakena, Rapa Nui we can say: No more marae.

Key publications of research carried out by Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin

The recent article on ritual spaces on Rapa Nui is the product of years of research on Polynesian ritual spaces, including fieldwork on four archipelagos, beginning in the mid-1980s. Paul Wallin and Helene Martinsson-Wallin were, together with Sonia Haoa, key investigators during excavations around Ahu Naunau at Anakena, Rapa Nui, in 1986-88.

A study of the ceremonial stone structures of Rapa Nui was the subject of Helene Martinsson-Wallin Ph.D. in 1994, and Paul Wallin's Ph.D. thesis was a similar study of marae ruins in the Society Islands in 1993. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, they undertook archaeological excavations on Rapa Nui, on Christmas Island and on Huahine, before expanding westward into the Kingdom Western Samoa.

Some of their field reports from excavations on Easter Island and on Huahine, Society Islands, can be found HERE (new link!), under the heading The Kon-Tiki Museum Fieldwork and Archival Series.

See below for a review of their key publications.